The Buddhist Sangha of Bucks County was delighted to welcome David Slaymaker on Monday, December 15th, for a special session of meditation and Dharma teachings on practicing with the firth precepts of intoxicants.

David, a dedicated practitioner in the Dharma Drum Mountain lineage of Master Sheng Yen, delved into how to practice with the precept through the lens of Chan Buddhism.

We hope you found the meditation and the teaching helpful and consider a donation (donna) to the Buddhist Sangha of Bucks County.

Introduction and Guided Body Scan Meditation

The Fifth Precept: Intoxication and Choice

In the first part of the talk, David Slaymaker introduces the fifth Buddhist precept—refraining from intoxicants—and explores it far beyond a simple rule about alcohol or drugs. He situates the precepts as the foundation of the Buddhist path, emphasizing that virtue comes first, supporting meditation and ultimately giving rise to wisdom. Far from being a side topic, the precepts are presented as essential to a deep and stable practice.

David examines what “intoxication” really means, drawing on traditional Buddhist teachings and everyday experience. Intoxication is not only about substances that cloud the mind, but anything that causes heedlessness, dulls awareness, or pulls us away from clear seeing. While alcohol and drugs are the traditional focus because they weaken mindfulness and make it easier to harm others, David broadens the discussion to include many socially acceptable forms of escape—busyness, entertainment, food, shopping, travel, fantasy, and even constant socializing.

The key question, he suggests, is not what we are doing, but why and how we are doing it. Many activities are healthy and necessary, yet they can become intoxicating when they are used to avoid discomfort, escape ordinary life, or temporarily alter how we think and feel. In this way, intoxication is revealed as a deeply human response to suffering and unease with the mind as it is.

Drawing from both Theravāda and Chan perspectives, David highlights that the heart of the fifth precept is choice. Without practice, people often have no alternative but to seek relief through sensual pleasure and distraction. With practice, however, a different option becomes available—meeting pain directly with awareness, clarity, and wisdom. This higher choice goes against the cultural stream but leads to genuine well-being rather than temporary relief.

This talk invites listeners to reflect honestly on their own habits, to see where intoxication may be operating subtly in daily life, and to consider how Buddhist practice offers a deeper, more liberating response to suffering.

Listen to the full talk to explore how the fifth precept opens into wisdom, clarity, and true freedom.

In the 2nd part of the talk, David Slaymaker explores a central truth of Buddhist practice: how to suffer less… Whether people turn to intoxicants, distractions, or spiritual practice, the underlying motivation is the same. The difference lies in the method. Escaping discomfort may bring temporary relief, but it does not lead to freedom. Practice, on the other hand, offers a skillful and compassionate way to meet suffering directly.

David emphasizes that the heart of the practice is simple and embodied—returning attention to the body and its changing sensations. The body anchors us in the present moment, the only place where liberation can be found. Thoughts may wander, emotions may surge, but presence in the body allows us to stay grounded in what is actually happening.

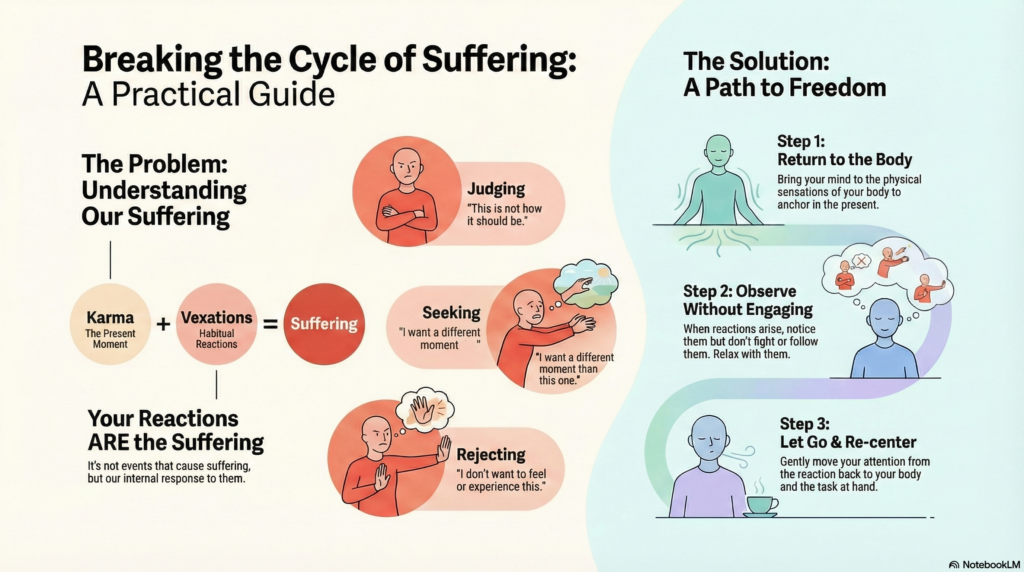

When suffering arises, our habitual reactions of judging, seeking, and rejecting intensify the pain. David explains that suffering is not caused by circumstances themselves, but by how the mind reacts to the present. Rather than trying to suppress these reactions, practice invites us to become aware of them and gently disengage—letting them arise, letting them be, and letting them go.

Habitual reactions are not failures or obstacles; they are the path itself. Each time they appear, there is an opportunity to practice awareness, patience, and compassion. Over time, these patterns are seen for what they are: conditioned habits that arise and fade when not fed.

This talk offers a grounded, accessible exploration of how embodied awareness, kindness toward ourselves, and a willingness to stay present—especially when things are uncomfortable—can gradually lead to greater clarity, calm, and freedom.

Listen to the full talk to explore how this practice unfolds in daily life.

Q&A Summary — David Slaymaker

In the question-and-answer session following the talk, participants explore how the themes of intoxication, intention, and presence apply in everyday life and formal practice.

One question focuses on the difference between healthy absorption in activities—such as running, art, cooking, or sports—and escapism. David responds that the distinction lies entirely in intention. Being fully engaged in an activity, where the mind is clear and present, can be joyful and wholesome. However, if an activity is used compulsively to avoid discomfort, loneliness, or unhappiness, then it functions as an intoxicant. The key inquiry is whether the activity enriches life or serves as a way to avoid facing one’s inner experience.

Another question addresses the concern that accepting the present moment might mean passivity or resignation, especially in difficult life situations. David clarifies that acceptance does not mean approving of harm or refusing to improve one’s circumstances. Rather, it means clearly seeing and fully feeling what is already present without adding judgment, agitation, or reactive thinking. From this clarity, wise planning and skillful action become possible. Practice, he emphasizes, is not passive—it is often more engaged, because it requires the courage to stay present with discomfort in order to respond wisely rather than react impulsively.

A participant then asks about the relationship between sitting meditation and daily life, using the example of physical discomfort on the cushion. David affirms that learning to “sit with” discomfort in meditation trains the capacity to be with unpleasant experiences off the cushion as well. He refines the language slightly, preferring “relax with it” rather than “endure it.” Letting sensations and reactions arise without immediately trying to fix or escape them builds the skill of non-reactivity that carries directly into daily situations.

The discussion continues with an exploration of how practice differs on the cushion versus in daily life. In formal meditation, the method is clearly defined and everything else is gently let go of. In daily life, however, the “method” is the task at hand, requiring broader awareness and discernment. David explains that practice is not about eliminating thoughts, but about being free from unskillful thinking while making use of thoughts that are helpful, appropriate, and responsive to the situation.

A final question raises a subtle but important concern: can meditation itself become a form of escape? David answers candidly that yes, it can. Practice can become intoxicating when it is used to suppress, avoid, or escape from one’s lived reality. He shares from personal experience how striving to become a “good meditator” can lead to rigidity and disconnection from the true purpose of practice. What matters is not constructing an identity around meditation, but honestly examining one’s intention: whether practice is being used to open fully to the present or to create distance from it.

David concludes by emphasizing that the fruits of practice emerge when striving softens and one is willing to meet experience directly—on the cushion and in life. When this alignment becomes clear, the boundary between meditation and daily living begins to dissolve, revealing practice as a path of genuine freedom rather than another form of escape.

Listen to the full Q&A to hear these reflections unfold in real time.

David’s journey in Buddhist practice began in 1992 with Soto Zen, leading him to study Chan with Master Sheng Yen in 1995. He has shared his knowledge and experience by leading numerous Dharma talks, meditation classes, and retreats at various centers, including the Chan Meditation Center, Dharma Drum Retreat Center, and DDMBA New Jersey. Outside of his practice, David is a biology professor in New Jersey, where he lives with his wife Dr. Rebecca Li. who is also a teacher that visited our sangha

You can find more information about David at chancenter.org

Visit ddmbanj.org 2nd Sundays and learn how to apply Chan practice to daily life.

Your donations help us support our visiting teachers. We hope you found the meditation and the talk insightful and consider supporting us in any way you can!