Patience with Others

Discussion led by Phil Brown, President; and Janet Weathers, Program Committee

Introduction to the Importance of Patience on the Buddhist Path

The parami of Khanti, or paramita of Ksanti, is the perfection of Patience. In Buddhism it is often defined as forbearance, endurance, acceptance, or forgiveness, but according to its Pali roots it may be best defined as “willingness.” In the Mahayana tradition of Buddhism it is said that there are three dimensions to this practice that we will be examining over the next few weeks: Practicing Patience with Others Patient Perseverance with Ourselves and Obstacles Patient Acceptance of the Path

In ordinary language, what do we typically mean by ‘having patience’? For example: ‘Waiting patiently for someone else to do something or finish doing something so we can have our turn.” Other definitions?

In Buddhism, patience has a different, deeper meaning that supports the Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path. It is one of the ten Paramis (perfections or attainments) that evolve from and come into being through practice of the dharma.

- The truth of suffering [Human life is characterized by suffering, dissatisfaction, anguish.]; (Dukkha)

- The truth of the origin of suffering [It is possible to understand the origins of suffering.] (Samudāya)

- The truth of the cessation of suffering. [It is possible for us to end suffering.] (Nirodha)

- The truth of the path to the cessation of suffering. [Practicing the Eightfold Path.] (Magga)

To summarize how and why patience is important to these truths: We need patience born of wise intention to see clearly and deal with the clinging, grasping quality of human that life. This creates the conditions for the end of suffering and discontent, and brings forth a felt sense of generosity, kindness and resolve to live more in accord with the Buddhist path.

In Buddhism Without Beliefs Stephen Batchelor talks about the truths not as propositions to believe, but “challenges to act” in the course of everyday life. We need a calm and clear acceptance of what is happening in the moment, which takes both patience and perseverance when craving and avoidance arise. Letting go of these afflictions leads to a deeper appreciation of life and the path of compassion.

How Patience Can Inform our Practice

In a recent dharma talk, Phillip Moffitt carefully details how we can use our heart to have patience with what arises in the mind (“How Patience and Resolve Cultivate Equanimity”, March 22, 2017: dharmaseed.org/talks/audio_player/139/39940.html)

Patience is the ability that allows us to stay with the mental, physical and emotional states that are difficult or challenging. Moffitt emphasizes that it is not passive – waiting around for something to happen. Patience is an energetic endurance that needs to be cultivated. It embraces the willingness to start over when we lose our breath or other object of meditation; it allows us to be with the feelings of failure, restlessness, and impatience for success that characterize our life and practice. Patience is a virtue, not just an attitude.

When we sit or live with patience, we are willing to start where we are at, soften into our experience, and develop a practice, a way of life that supports the other paramis and endures.

Patience and Wisdom

The parami of wisdom tells us where we want to go on the path. It is in stark contrast to an ‘only results matter’ attitude and philosophy. In cultivating wisdom, we concentrate on the value of the truth of our experience in the context of the Buddhist path. Wise intention invites us to be in the moments of our experience with a spirit of loving kindness, a non-harming attitude, joyful empathy and equanimity.

The formula: Patience supports mindfulness, mindfulness powers discernment, and discernment leads to wisdom.

To aid our practice, patience needs to rest on a bedrock of these core values. As we move through life, we plant seeds from moment to moment that help create the causes and conditions of subsequent moments (karma). Patience helps us govern how we meet the intention to talk or act in accordance with these core values, the basis for Buddhist morality and guidance. We are not responsible by ourselves for all of our thoughts and the sea of impulses that push us in mindless or harmful directions for ourselves or others. But we can be responsible for how we relate to our thoughts and actions so that we can learn from them while resting on the bedrock of core ethical values (the Bhramaviharas, the Eightfold Path), and performance values (resolve, persistence, perseverance).

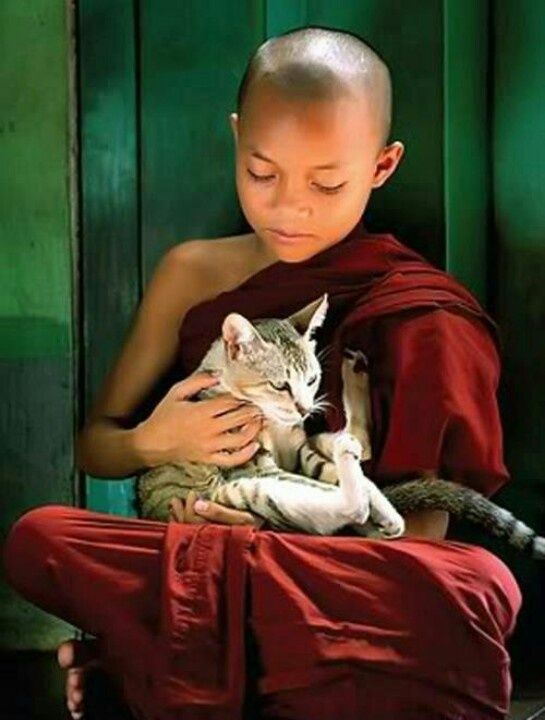

Patience with Others

Patience can be both internal and external. Internal patience is patience with ourselves. External patience is patience with others. Let’s explore together our experience of some of the conditions with others in our lives that result in impatience or call forth patience.

- In your small group remember a time that impatience with someone else’s behavior or interaction with you led to dissatisfaction, suffering or unhappiness. In retrospect, how might patience have led to more kindness and support (and a different outcome)?

- Can you remember a time when exercising patience changed how another person related to you or reacted to you? How did that feel? How did you talk to yourself to keep from reacting in a way that would have sown the seeds of additional suffering or disappointment? How did the idea of a solid self that needs to be buttressed or protected show itself? What impulses or needs did you overcome? What sources of wisdom did you use? What core values did you rely on.